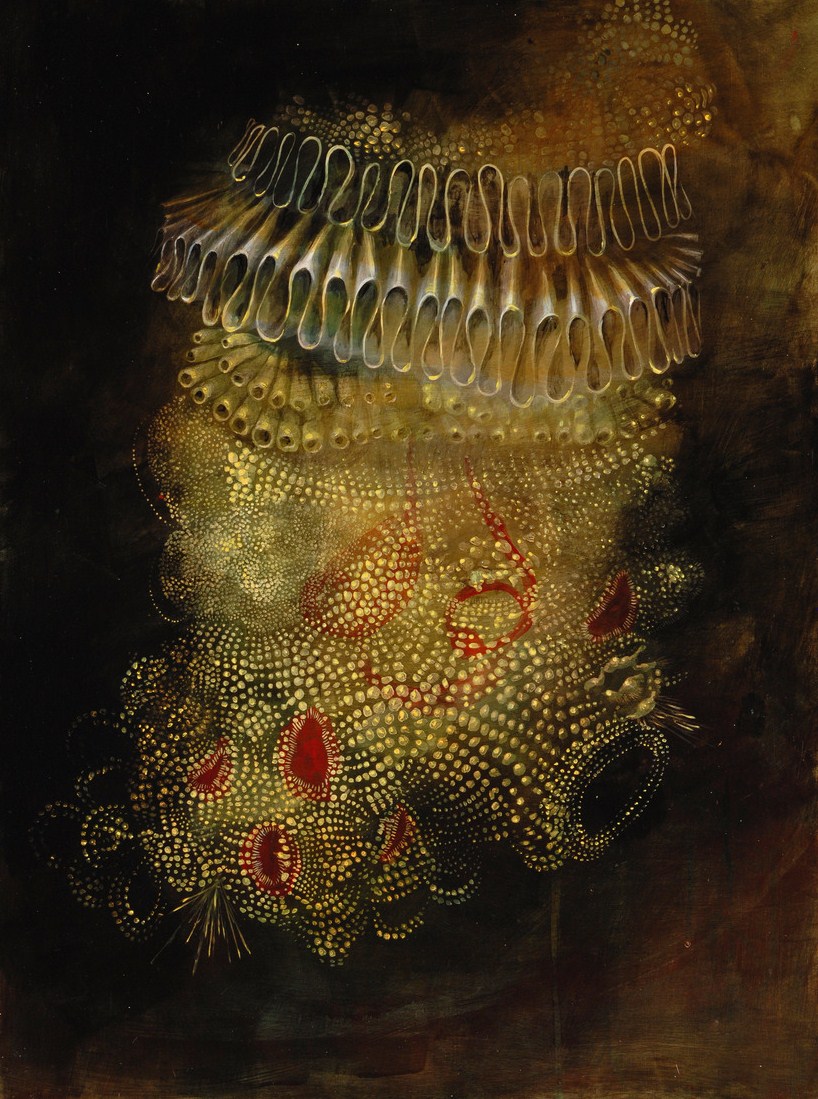

out of the strong came forth sweetness

Aucocisco Gallery, 2007

Nicole Duennebier’s painting reaches into a primordial deep-sea darkness to pull out luminescent patterns dotting undulating shapes. Organic masses ripple out from the realm beyond our visual perception. Millipedes meander at the foot of a ruffling hive while hovering insects dart out from an interior world of the canvas into the exploratory spotlight the artist shines on her not-so-still still life.

The young Portland painter, now exhibiting “Bitters” at Aucocisco Gallery, creates still life out of such unorthodox subjects in part by her extraordinary hand. Brushstrokes and color are delicately arranged against an equally-tempered and inviolate darkness. Acrylic is applied to panel with such precision that the tenebrous technique evokes comparisons of the shadow and drama characteristic of Baroque painting. Duennebier cites the Carravagisti, adherents of a short-lived but popular school of painting after the great master, as a stylistic influence.

“I Heard He Grew Up in the Forest” is a totemic rendering of wild game with images of human as hunter towering above the running prey. The images flow into one another in a sculptural composition as though the scene is a carved embellishment on a monarch’s mirror. The vanity of our perceived place on the food chain is balanced when Duennebier sets the object against an ominous and infinite space that reveals our current victories to be like blossoms on a tree, destined to fall back to the ground from where they came.

A human presence obliquely remains when Duennebier turns to still life. “Hunting Hotbed” is a beautifully repulsive snapshot of an unforgiving pool of water where a dead rabbit stagnates in the corner and vicious arrows are left protruding from unintended targets. The surrounding seaweed is reminiscent of an Elizabethan ruffled collar. Throughout her pieces, the artist anthropomorphizes these moments of erupting birth and death with vestiges of human plumage. Fish roe are reminiscent of strings of pearls and lizards take on the personalities of a gorging ruling class.

In “Star of Thelma,” strings of gleaming jewels hang like a diamond chandelier or spring from an opulent cosmos. Zygotes edge toward the gravitational center of reflective spheres that simultaneously appear to be both patterns of lace and the paths of subatomic particles. Equally organic and decorative, technical and emotional, the piece is a formal victory for the artist.

“Perpetuum Flea Circus” features dancing colored lights at the base of the canvas to resemble an amusement park. Superimposed are two enormous fleas, rendered in thin-lined highlights. They sit symmetrically back to back in a manner resembling a Rorschach test image. More outlined invertebrates make their way up the canvas on a bridge of banana leaves into a wispy mass looking much like a wig entangling coral configurations and spinning shapes. The same compositional relationship is used in “Weaver Birds” when the wig becomes a nest and the circus becomes a fallen wolf. The flock gather around the dead beast and sing a song of mourning. There lies both action and death outside the safe haven of creation as the nest spills out into the dynamic ground. Duennebier is most successful when she reveals these truths in classical fashion as she does so without a hint of irony or nostalgia. Her work means something today, even if it visually coddles you in the comfortability of yesterday.

Evolving tastes and societal shifts are reflected in the history of the still life. In Duennebier’s contemporary vision, the reflection is of evolution itself. The orgiastic feeding frenzies and bulbous mold growths are nature consuming itself, momentarily distinct from a Heraclitean fire. Her still life subject reflects our developing understanding of systems, of our interpretation of the world around us through a scientifically grounded metaphor of interconnectedness. Her ecology of composition is infused with a classical drama because we are there looking into these mysterious worlds and our conscious perception fears the depths of reality beyond its inherent capabilities.

The drama is one of anxiety brought upon by our increasing understanding that we do not understand. The “Bitters” show succeeds because it assuages that anxiety with a detached beauty that appeals to our senses. We can plunge into unseen ocean depths thanks to our technological manipulations so that we may finally see an ancient world that goes on with or without us, but we can only see it through the glass. Nicole Duennebier’s work mutes the overwhelming roar of creation so that we can step onto the observation deck and catch a fleeting glimpse of our role in that creation as a species bound by our senses and curious by way of our consciousness.

By IAN PAIGE | March 7, 2007